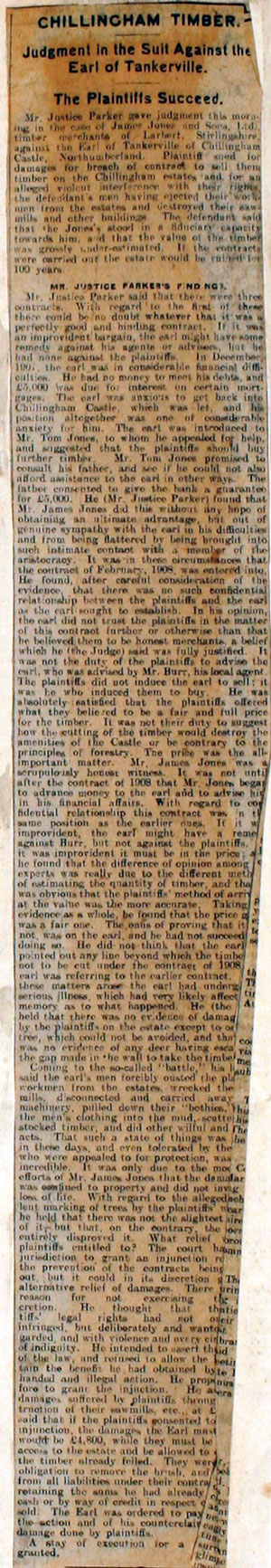

CHILLINGHAM TIMBER. Judgement in the Suit Against the Earl of Tankerville. The Plaintiffs Succeed. Mr. Justice Parker gave judgement this morning in the case of James Jones and Sons, Ltd., timber merchants of Larbert, Stirlingshire, against the Earl of Tankerville of Chillingham Castle, Northumberland. Plaintiff sued for damages for breach of contract to sell them timber on the Chillingham estates and for an alleged violent interference with their rights, the defendant's men having ejected their workmen from the estates and destroyed their sawmills and other buildings. The defendant said that the Jones's stood in a fiduciary capacity towards him, and that the value of the timber was grossly under-estimated. If the contracts were carried out the estate would be ruined for 100 years. MR. JUSTICE PARKER'S FINDINGS. Mr. Justice Parker said that there were three contracts. With regard to the first of these there could be no doubt whatever that it was a perfectly good and binding contract. If it was an improvident bargain, the earl might have some remedy against his agents or advisors, but he had none against the plaintiffs. In December, 1907, the earl was in considerable financial difficulties. He had no money to meet his debts, and £5,000 was due for interest on certain mortgages. The earl was anxious to get back into Chillingham Castle, which was let, and his position altogether was one of considerable anxiety for him. The earl was introduced to Mr. Tom Jones, to whom he appealed for help, and suggested that the plaintiffs should buy further timber. Mr. Tom Jones promised to consult his father, and see if he could not also afford assistance to the earl in other ways. The father consented to give the bank a guarantee for £5,000. He (Mr. Justice Parker) found that Mr. James Jones did this without any hope of obtaining an ultimate advantage, but out of genuine sympathy with the earl in his difficulties and from being flattered by being brought into such intimate contact with a member of the aristocracy. It was in these circumstances that the contract of February, 1908, was entered into. He found, after careful consideration of the evidence, that there was no such confidential relationship between the plaintiffs and the earl as the earl sought to establish. In his opinion, the earl did not trust the plaintiffs in the matter of this contract further or otherwise than that he believed them to be honest merchants, a belief that he (the Judge) said was fully justified. It was not the duty of the plaintiffs to advise the earl, who was advised by Mr. Burr, his local agent. The plaintiffs did not induce the earl to sell; it was he who induced them to buy. He was absolutely satisfied that the plaintiffs offered what they believed to be a fair and full price for the timber. It was not their duty to suggest how the cutting of the timber would destroy the amenities of the Castle or be contrary to the principles of forestry. The price was the all-important matter. Mr. James Jones was a scrupulously honest witness. It was not until after the contract of 1908 Mr. Jones began to advance money to the earl and to advise him in his financial affairs. With regard to confidential relationship this contract was in the same position as the earlier ones. If it was improvident, the earl might have a remedy against Burr, but not against the plaintiffs. If it was improvident it must be in the price; and he found that the difference of opinion among the experts was really due to the different methods of estimating the quantity of timber, and that it was obvious that the plaintiffs’ method of arriving at the value was the more accurate. Taking the evidence as a whole, he found that the price given was a fair one. The onus of proving that it was not, was on the earl, and he had not succeeded in doing so. He did not think that the earl had pointed out any line beyond which the timber was not be cut under the contract of 1908; the earl was referring to the earlier contract. Since these matters arose the earl had undergone a serious illness, which had very likely affected his memory as to what had happened. He (the Judge) held that there was no evidence of damage by the plaintiffs on the estate except to one yew tree, which could not be avoided, and that there was no evidence of any deer having escaped by the gap made in the wall to take the timber away. Coming to the so-called "battle," his lordship said earl’s men forcibly ousted the plaintiff’s workmen from the estates, wrecked their sawmills, disconnected and carried away their machinery, pulled down their "bothies, " threw the men's clothing into the mud, scattered the stocked timber, and did other wilful and wanton acts. That such a state of things was possible in these days, and even tolerated by the police, who were appealed to for protection, was almost incredible. It was only due to the moderating efforts of Mr. James Jones that the damage done was confined to property and did not involve loss of life. With regard to the alleged fraudulent marking of trees by the plaintiffs workmen, he held that there was not the slightest evidence of it, but that, on the contrary, the evidence entirely disproved it. What relief were the plaintiffs entitled to? The court had the ample jurisdiction to grant an injunction restraining the prevention of the contracts being carried out, but it could in its discretion grant the alternative relief of damages. There was every reason for not exercising this discretion. He thought that the plaintiffs’ legal rights had not only been infringed, but deliberately and wantonly disregarded, and with violence and every circumstance of indignity. He intended to assert the authority of the law, and refused to allow the Earl the benefit he had obtained by high handed and illegal action. He proposed therefore to grant the injunction. He assessed the damages suffered by plaintiffs through the destruction of their sawmills, etc., at £2,300, and said that if the plaintiffs consented to waive the injunction, the damages the Earl must pay them would be £4,800, while they must be given free access to the estate and be allowed to carry away the timber already felled. They were under no obligation to remove the brush, and were freed from all liabilities under their contract, the Earl retaining the sums he had already received in cash or by way of credit in respect of the timber sold. The Earl was ordered to pay the costs of the action and of his counterclaim for alleged damage done by plaintiffs. A stay of execution for a fortnight was granted.

Chillingham Church photographed in 1986.

The carved alabaster figures of Sir Ralph Grey and his wife Elizabeth in the south chapel of St. Peter's Church, Chillingham. He died in 1443. Photograph taken in 2009.

Chillingham Castle. The Greys at Chillingham were descended from the Greys of Heton. Sir Ralph Grey, knighted in Leicester in 1425, died at Chillingham and has a very splendid tomb in the church. The Chillingham branch ran out of male heirs. Mary Grey an only daughter married Charles Bennett in 1695. He was created first Earl of Tankerville in 1714, (although the title had been used by his father-in-law 13 years earlier) and their descendants became the Tankervilles at Chillingham. The Milfield Greys, who were convinced that they were descended from Sir Ralph through another male line, felt themselves to be more authentic Greys than the Tankervilles. A family story is told of a Tankerville visiting Milfield Hill; observing the scaling ladder carved above the door and saying " I see you have our crest" and of a Milfield Grey replying: " On the contrary you have ours. " Although the Milfield Greys used the scaling ladder crest it was quite unauthorised since they had been unable to find documentary evidence to prove a direct connection to their noble neighbours. However generations of Milfield Greys have visited Sir Ralph's tomb at Chillingham and claimed descent from him. They have also been interested in the fate of Chillingham Castle and the estate and there are number of cuttings in the scrapbooks about it. It isn't known if any Milfield Grey was an estate manager of Chillingham and the cutting below has a Mr. Burr as agent. It is possible that the Milfield Greys had a connection to the Tankervilles through politics. Henry Grey Bennet, the fourth earl of Tankerville (1743–1822), like John Grey of Dilston, supported parliamentary reform.