Above: Page 39 of George Grey of Milfield's scrapbook with a cutting about the death of Henry the third Earl in 1894. The engraving made from a portrait by W.& D. Downey. Right: uncredited portrait from the National Portrait Gallery.

A carte de visite by W & D. Downey Photographers, 9, Eldon Square, Newcastle upon Tyne. Written on the back in John Grey's handwriting : "1. Earl Grey, 2. John Grey, and 3. Alderman Laycock". They are attending an agricultural show, possibly the Royal Agricultural Show which used to be held on Newcastle Town Moor.

The Milfield Grey's and Howick Greys.

John Grey of Dilston supported the Whig cause and was said to have been rewarded by being given the job of managing the Greenwich Estates.

From the mid 19th century the Milfield Greys were agents for the Howick estates. Correspondence about the estates can be found in the Durham University archives here.

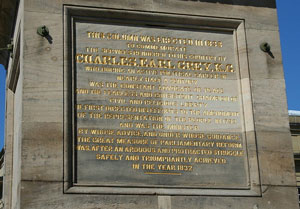

Charles 2nd Earl Grey (13 March 1764 – 17 July 1845), was Prime Minister from 22 November 1830 to 16 July 1834. He was responsible for the 1832 Reform Act and the abolition of slavery. He is famous for Earl Grey tea and, since the 2008 film, for his affair with the Duchess of Devonshire. He is commemorated by Grey's Monument at the top of Grey Street in Newcastle upon Tyne, which consists of his statue standing on a 135 ft high column.

Extracts from John Grey of Dilston's will:

To my son George A. Grey ... The print of Charles Earl Grey, from a portrait by Sir Thos Lawrence, given to me by his Countess. The portrait of Lord Howick, now Henry Earl Grey, painted by Mole. The Portraits of Charles James Fox & of my late friends Charles William Bigge, William Ord M.P. and John Taylor. The engraving of the passing of the Reform Bill and ...Also, the Statue of Charles Earl Grey, from the cast by Bailey.... And to my son Charles Grey Grey, ... the print of Charles Earl Grey by Jackson. The print of Sir George Grey Bart by Grant. The prints of the late Lord Durham & young Lambton, by Lawrence and those of the Revd Henry Grey & of my old master Dr. Tate. Also the column with statue of Earl Grey, which I had made as a model for the Grey column in Newcastle ...

Grey's monument in Newcastle. Designed by E H Bailey in 1835. Photo by Tagishsimon -Wikimedia Commons.

Photo. by Peter Clarke from Wikimedia Commons.

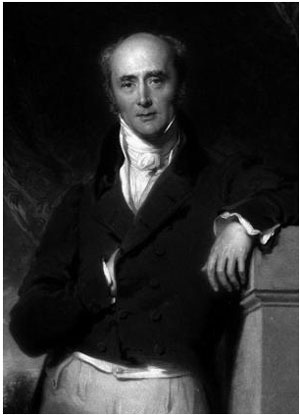

Charles 2nd Earl Grey, painted in 1928 by Sir Thomas Lawrence. From Wikimedia Commons.

Above left: Watercolour by Mole of Henry George Grey, 3rd Earl Grey (28 December 1802 – 9 October 1894), Charles' eldest son, who became a politician like his father. He had no children and was succeeded by his nephew Albert Grey the 4th Earl (28 Nov 1851-29 Aug 1917) who became Governor General of Canada.

Charles Earl Grey by John Jackson, RA, born 1778 - died 1831 in V. and A. collection.

Grey's monument from thetyneandbeyond.blogspot.com

The Reform Bill Receiving the King's Assent by Royal Commission, 7 June 1832 by William Walker, by Samuel William Reynolds Jr, after Samuel William Reynolds mezzotint, published 1836. National Portrait Gallery.

Left: Page 67 of the Dixon- Johnson scrapbook. An article dated 16 October 1946 which describes the 100 year old St James at Morpeth and the dedication of the Grey Chapel to the Rev. Francis Richard Grey (13 March 1814- 22 March 1890), who was the 6th surviving son and 14th child of Charles 2nd Earl Grey.

He was Canon of Newcastle and Rector at Morpeth.

Left: Page 35 of the Dixon-Johnson scrapbook contains a cutting from WW2 about the death of Captain George C. Grey, Liberal M.P. for Berwick who was killed in action. The son of General W. H. Grey "who was a cousin of the late Viscount Grey of Fallodon"

George Charles Grey (2 December 1918- 30 July 1944) was the youngest member of the House of Commons. He died in Normandy.

A W. H. Grey aged 58 can been found living at 12 Hobart Place , London, WC1 in 1934, with George C. and Robin Grey aged 15 and 10.

The father of Edward Grey of Fallodon, had no siblings so it is difficult to see how W. H. Grey can be his cousin. If there is a connection it must be farther back.

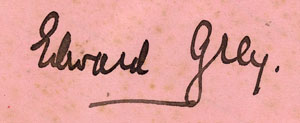

The Milfield Greys maintained contact with the Howick and Fallodon Greys at least until the early 1900s. In 1900 Earl Grey sent Jock Grey a silver inkstand for his 21st birthday. It was mentioned in the newspapers, who listed the presents, and it still has a little note inside one of the ink pots, recording that it was from Earl Grey. The titled Greys also appear as invited guests at the wedding of Milfield children; although it is not recorded if they actually attended. At Freddy Grey's wedding in 1907: "The Governor-General of Canada and Lady Grey, Lord and Lady Howick"; and at Ivar Grey's wedding in 1910: "Lord and Lady Howick, the Right Hon. Sir Edward Grey, His Excellency the Governor General of Canada (godfather to the bridegroom) and Countess Grey." In 1916 the bride's father, Sir Francis Blake, became Edward Grey's successor as MP for Berwick.

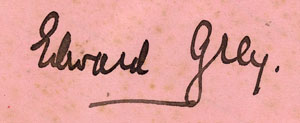

Right: Edward Grey's signature from Kathleen Grey nee Blake's autograph album.

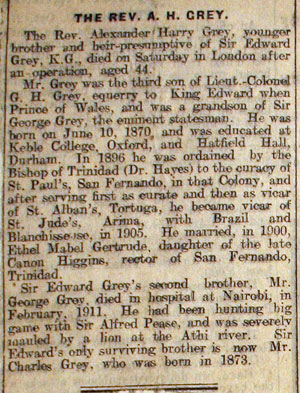

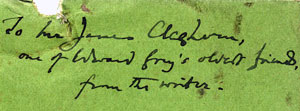

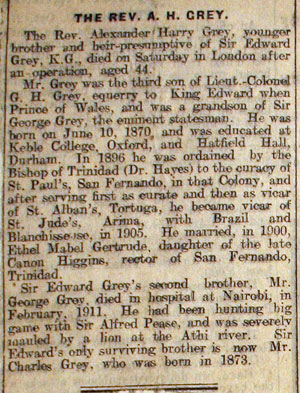

Left: Page 40 of Dixon-Johnson scrapbook:

The death of the Rev. A. H. Grey, brother of Sir Edward Grey of Fallodon in 1914. Sir Edward Grey had 3 brothers. George Grey was killed by a lion in Africa in 1911. The Rev. Harry Alexander died after an operation in 1914, and the surviving brother Charles was killed by a buffalo in 1928. Since Sir Edward had no children only his 3 sisters survived him.

He left Fallodon to Capt. Cecil Graves the son of his sister Alice.

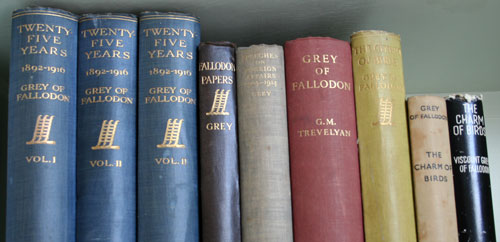

Post WW1 Milfield Greys appear to have more enthusiasm for ornithology than politics and several copies of Edward Grey of Fallodon's "The Charm of Birds" from 1927 can be found amongst their possessions.

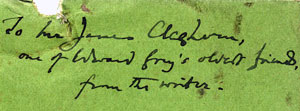

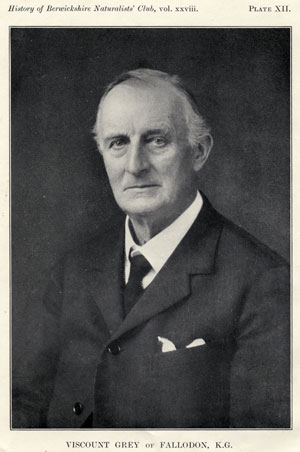

Grey of Fallodon. (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933) Photograph from opposite Page 1 of his obituary by R. C. Bosanquet, for the History of the Berwickshire Naturalist's Club, printed by Neill and Co. in Edinburgh. This copy is dedicated to James Cleghorn, who worked for George Grey and Sons.

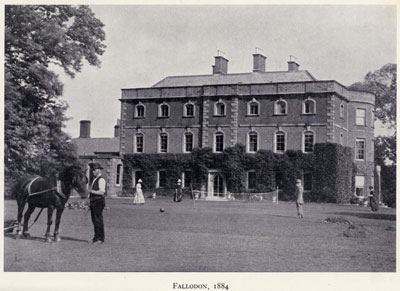

Fallodon in 1884. Photograph from opposite page 3 of "Grey of Fallodon" by G. M. Trevelyn, published by Longmans, Green & Co. in 1937.

OBITUARY NOTICE VISCOUNT GEEY OF FALLODON, KG. IN EDWARD GREY this country has lost a wise and fearless statesman, a lover of nature and of letters, an exemplar in their highest form of the virtues in public and private life that characterise the ideal country gentleman. This is not the place for a review of his services to the State. It will be enough to tell in outline the story of his life in relation to the Borderland that bred him. The Greys of Fallodon are a younger branch of the house of Howick, and that is an offshoot of the ancient family that held Chillingham from the fifteenth century onwards. The home that moulded the character of two great statesmen—for the second Earl Grey, champion of the Reform Bill, was born and grew up at Fallodon—has a place in national history. The first house there was built in the mid-seventeenth century by Ralph Salkeld, a merchant of Berwick, of the family that owned Huln Abbey and Rock. Its heads were royalist, he a Puritan, but whatever their principles the Salkelds seem to have been planters and gardeners, reproducing wherever they went the walled orchards that the Carmelites had left behind them at Huln. His son inherited his tastes, for in 1694, when Bishop Nicolson wrote notes on Northumberland for a new edition of Camden's Britannia, he praised "the improvements in gardening and fruitery at Fallodon . . . hardly to be equalled on the North Side of Tyne," mentioning peaches, plums, and pears. The garden he admired is still there, a square with angles set to the four points of the compass, and high brick walls, sheltered from the prevailing south-west wind by the old house and stables which stand on rising ground, and from north and east by trees. The tradition of skilful fruitgrowing has been unbroken; the span of the last three head gardeners' lives covers about 160 years. Edward Grey added a glass orchard-house, so that Nicolson's words are still true: 2 " Fruit is produced here in as great perfection as in most places in the South." Fallodon was sold in 1704 to Thomas Wood, who must have built the red-brick house with stone facings and extended the garden. The mature trees that in 1724 made Fallodon noticeable in a bare landscape, catching the eyes of travellers on the North Road, were no doubt of his predecessors' planting, but we may guess that he laid out the long, narrow pond which Edward Grey gave as a home to his ducks—a "canal" such as the early eighteenth century loved. When he died in 1755 Wood left to his gardener an annuity for life "if he so long shall continue to do the duty of a gardiner at Falloden, working in and taking care of my gardens there to the best of his ability." His daughter and heiress was Hannah, widow of Sir Henry Grey of Howick, through whom Fallodon passed to her fourth son, Charles, a distinguished soldier who held high commands in the American War and was raised to the peerage in 1801 as Baron Grey of Howick, and in 1806, shortly before his death, was created Viscount Howick and Earl Grey. He made Fallodon his home for forty years, and here his eldest son, the great Whig statesman, and seven other children grew up. Some of the finest trees, notably the silver fir that soars above all its neighbours in the lower garden,* are memorials of his ownership. He was succeeded by his second surviving son, General Sir Henry Grey, who planted the long avenue, and he in 1845 by the son of his sailor brother. Sir George Grey (1799-1882), who now inherited Fallodon, was an outstanding and much loved figure in Victorian politics—Home Secretary for most of the period 1846-66. He retired from Parliament in 1874, and at the end of that year his only son, Lieut.-Colonel George Grey, who had served in the Crimea and been equerry to the Prince of Wales since 1859, died in the prime of life. Mrs Grey, daughter of Lieut.-Colonel Pearson, a woman of character and charm, survived him till 1905. Of their seven children Edward was the eldest, born 25th April 1862. Sir George devoted his remaining years to the upbringing of his grandchildren, whose home had always been at Fallodon. After a life of public service he was still young in mind and * Illustrated in Lord Grey's Twenty-five Years, in p. 240. A companion tree showed 125 rings when it fell in 1894. 3 vigorous in body. Edward, four years older than his next brother, was often the companion of his rides and walks, and during those formative years must have absorbed unconsciously something of the principles that had governed the old man's life. The love of wild nature and adventure that carried his brothers to distant parts of the Empire was present in Edward too, but when he was called to serve his country, and eventually sacrifice his health in London office work, he did not hesitate. His master-passion from those early days was angling. In his book on Fly Fishing (1899) he tells how he began when seven years old in the Fallodon burn, and gradually traced it further until one day in a pool near its mouth, "a distant land where things happened otherwise than in the world nearer home," he landed a fresh-run sea-trout of three pounds; how as a school¬boy at Winchester he learned the art of the dry fly on much-fished water, and used it with success on less sophisticated trout in the Highlands; how salmon fishing taught him further lessons of endurance and self-control; and how in later years to the pleasure of success was added that of contemplation, of entering into the moods of Nature. He excelled at games,* became a good shot, and was entered early to hunting, but cared little for it. From Winchester he went to Balliol in 1880, and had completed his second year there when his grand¬father died, and he found himself master of a pleasant estate with the choice of a way of life open. Natural instincts called him to open-air pursuits, family tradition to public service. He has told how, in 1884 "interest in all manner of serious things came suddenly. I began to read good literature, poetry excited me to enthusiasm. The same rush of interest applied itself to public affairs." Some of the seeds that now bore fruit were sown by Mandell Creighton, afterwards Bishop of London, a man of wisdom as well as learning, who had been vicar of Embleton and a close friend of his family for ten years. After a brief political apprenticeship Grey was chosen as Liberal candidate for the Berwick-on-Tweed division of Northumberland, and elected to Parliament at the age of twenty-three. He sat for the same constituency until July 1916, * At tennis he won the Amateur Championship five times between 1889 and 1898. In the contests for the M.C.C. Challenge Prizes he was placed first in 1896, and second thirteen times from 1889 to 1904. 4 when he was created Viscount Grey of Fallodon, and retired from public life a few months later, having served at the Foreign Office as Under-Secretary of State, 1892-95, and Secretary of State, 1905-16. Shortly before his first election, in October 1885, he married Dorothy, elder daughter of Mr S. F. Widdrington of Newton Hall. She shared and deepened his devotion to public duties, and equally his delight in wild nature. Field-glass in hand they studied the ways and learned the notes of birds, now in Northumberland, now at a fishing cottage on the Itchen,* to which they could escape during the session. They tamed squirrels and robins at Fallodon, and stocked the grounds with flowering and scented shrubs. During periods of exile in London parcels of flowers and sprays of leaves kept them in touch with the garden that, as he said, "they knew by heart." He had begun in 1884 to form a collection of ducks there, as Lady Waterford had done at Ford. In 1887 he excavated a new and larger pond and stocked it with Loch Leven trout, which throve, and with Salmo fontinalis, which soon disappeared. But this pond too has long been consecrated to water fowl, and most of his fishing at Fallodon was in a winding quarry, fed by springs, in which Loch Leven and rainbow trout managed to breed. It was characteristic of his determination and bodily poise that after his sight was much impaired he continued to fish there alone, though it would have been easy to miss his footing on the steep rocky bank. On familiar ground memory never failed him, and he moved with the confidence of one who sees well. He experimented also with trees. The main railway and a public road pass within a quarter of a mile of the house, and though roads were less noisy than they are to-day, there was heavy traffic on the railway. He gained seclusion and shelter by planting fifty acres that lay between, using many varieties of conifer, and learning in due course that trees from western North America, such as Tsuga albertiana, do well in our climate, being used to summer rain, while those from the eastern side, such as Tsuga canadensis, are far slower in growth. Thus the place became more and more a sanctuary, with the fox-proof * W. H. Hudson describes the cottage in his Hampshire Days. It had been lent to him for a summer, and he dedicates his book "to Sir Edward and Lady Grey, Northumbrians with Hampshire written in their hearts." 5 duck enclosure for its centre. Thirteen kinds of foreign ducks and ten of British have at different times been reared. Since the war Grey's aim was not to collect rare species, but to win the confidence of wild visitors which came and went. Lady Grey died in 1906. Deprived of her companionship, more and more cut off from country life, he laboured unremittingly against incalculable odds to preserve peace in Europe. "A moderate, patient, wise man, the biggest Englishman I have met," wrote the American ambassador to his President. And again, in the last week before the outbreak of war, Page described him as a "sad and wise idealist, restrained and precise in speech and sparing in the use of words, a genuine clear-thinking man whose high hopes of mankind suffer sad rebuffs but are never quenched." It was not rhetoric but candour and sincerity that made Grey's speech of August 3,1914, a trumpet-call to the Empire. He was on the brink of a serious illness when more than two years later he gave up the seals, having held them for a longer continuous period, and in darker days, than any Foreign Secretary before him. Retirement from office brought leisure, and fishing became possible again. For a time his eyesight seemed to improve. He began to share with a public that was weary of war the fruit of his observations in the open air, his reading and re¬flection. In the first of these self-revealing addresses, on " Recreation," he told an American audience how he had guided Theodore Roosevelt in Hampshire, and taught him to recognise English birds by eye and ear. The second in point of time, in some ways the most intimate of the talks afterwards printed in Fallodon Papers (1926), dealt with his waterfowl, and was delivered to his country neighbours, the members of our Club, in October 1921. It will always be a matter of pride that he honoured the Berwickshire Naturalists by holding the office of President, and preparing this address, spoken without notes —for reading had become difficult—yet perfect in form and full of accurate detail and cautious deductions. He thought it would not interest the general public, but it was so widely read and discussed that he was encouraged to write The Charm of Birds (1927), which has become a classic. These books and his political retrospect, Twenty-five Years (1925), were mainly written in the years of renewed happiness 6 following his marriage in 1922 with Pamela, Lady Glenconner. Her friendship and Lord Glenconner's had long played a great part in his life. Lady Grey, herself a writer, shared his love and understanding of birds, and his delight in Wordsworth. The Charm of Birds contains her beautiful description of the Dawn Chorus, and many references to her house at Wilsford. Fallodon had been burned in 1917, but was now rebuilt without the unbecoming third storey that had been added by the first Earl Grey to the well proportioned low house. It was a joyous place again until 1928, when two blows fell in quick succession—the death of Charles Grey, his only surviving brother, who had spent many years as an explorer in Africa, and of Lady Grey two months later. His world seemed shattered, for he was one of those "Whose master-bias leans "To homefelt pleasures and to gentle scenes." Yet his moral stature was such that he bore his afflictions without complaint, and was still the good landlord, the generous host and considerate friend that he had always been. He wrote but little after this. His talk was still lit up with unexpected quotations, for he had a retentive memory for things worth remembering, and his favourite authors ranged from Homer and Herodotus to P. G. Wodehouse. He delighted in good stories, as his published addresses show. He could adapt his conversation with quick sympathy to his listener's capacity, and was ready, as Walter Page noted, to discuss "any sort of thing that is big and interesting." In those years of failing health and eyesight he still performed many public duties. He became Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1928, and at his inauguration surprised his hearers by delivering from memory a Latin speech. He continued to serve as a director of the London and North-Eastern Railway Company; in 1905, when out of office, he had been chairman of the old North-Eastern. A Trustee of the British Museum, he was regular in attendance at meetings, with special interest in the Natural History departments. He served as a Vice-President of the Royal Zoological Society's Council, and was one of a committee of three empowered to manage the wild white cattle at Chillingham, when Lord Tankerville leased the park and the herd to the Society; a 7 fitting choice, for he was descended from the original owners, and the walk to Ross Castle, a lofty hill-fort overlooking Chillingham, with a sea of heather to the east and a view across woods to Cheviot on the west, was one of which he never tired. To the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty he gave such active support that the office of Vice-President was created for him. He had long been a member of the Fame Islands Association, gave generous help when funds were raised for the purchase of the islands and their transfer to the National Trust, and thereafter was a member of the sub-committee that administers them. To the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle-upon-Tyne he was a good friend, ever mindful of the needs of the Hancock Museum. At the age of seventy he seemed to think nothing of two successive nights in the train; he would leave Fallodon on Friday evening, attend a meeting of the governing body at Winchester on Saturday, and be in his accustomed place in Embleton Church on Sunday morning. "He was not unselfish, because he was selfless." During the spring and early summer of 1933 his health was visibly failing. After an illness of twelve days he died at Fallodon on 7th September—by common consent "a great Englishman." R. C. BOSANQUET.